One of my favorite stories about what it was like to see Star Wars: A New Hope when it was released in 1977 comes from my father. He went to see the film with his friend and roommate at the time, and when Vader’s Star Destroyer came into frame in the opening sequence, stretching on and on into infinity, the guy sank into his chair and shouted to the theater “Oh shit, this is it!”

I love that story because it elucidates something so significant about that first Star Wars film; when it first came out, no one had ever seen anything quite like it.

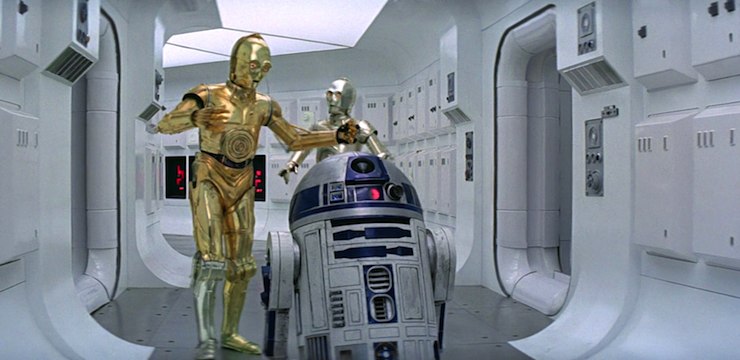

I’m not saying that no one ever made movies about space or put aliens in stuff or made model ships that they danced across black screens. But the scope of Star Wars, the detail that went into its world-building, was unprecedented at the time. The journey is well-documented—smudging vaseline on the lens of a camera to blur out the secret wheels under Luke’s landspeeder, using string to get R2-D2’s jack into the Death Star’s computer socket, five guys standing outside the Falcon’s cockpit set and manually shaking the thing when the ship was caught in the Death Star’s tractor beam. No one working on the film truly understood what their hard work was going into, the actors couldn’t get George Lucas to talk to them (he was too shy), and when the young director returned home from the shoot, he found that none of the special effects were up to snuff and scrapped every single one of them.

The fact that Star Wars got made at all is a miracle. The fact that it became the cultural phenomenon and touchstone we know today is exasperating to think about due to the sheer impossibility of it. This funny little space movie should have been a cult classic, a fond childhood memory that 70s and 80s kids inflicted on their own groaning children. And yet here we are, living in a world where no one hears the words “I am your father” without snickering behind their hand. Where “cinnamon bun” is a legit (though nearly impossible to recreate) hairstyle, and practically every child has pretended to wield a lightsaber against their siblings. Where these films have completed their third trilogy, with a growing spiderweb of television sprawling out in their wake, and multiple generations have rediscovered them by passing the experience down like a beloved heirloom.

Can you watch this movie with a clear head? For my part, it’s impossible. It’s imprinted on the backs of my eyelids, its soundtrack put me to sleep as a child, its wide reach found me some of my dearest friends. But why? Why this film? This was the point of investment, the place where the world decided how seriously it was prepared to take a strange mythic space opera that started with a scroll of yellow slanted text. If everyone had thought it was a cute kiddie film, the next movie would have been a weird story where Luke and Leia got into a mud fight and tried to snatch a snazzy crystal out from under Lord Vader’s nose. (I’m not fibbing—click the link.) It would have been a fantasy adventure like Legend or Willow, fun and silly and far from any Top 100 movie lists. So this is the real question: why did Star Wars work?

And the honest to goodness reason might be simpler than anyone is willing to admit. It’s because, practically speaking, Star Wars is a perfect movie.

Most people are going to be in two camps when I say this. The first camp thinks I’m crazy to issue a statement like that when there are movies out there made by super smart people like Stanley Kubrick and Céline Sciamma and David Lynch and Ava DuVernay and Federico Fellini. The second camp thinks I’m crazy to issue a statement like that when Empire Strikes Back exists. And both points of view are totally valid, I’m not disputing either of them. But the first Star Wars film accomplishes something very special, something rarely appreciated by art communities of any kind. (Don’t even get me started on the fact that this movie lost out to Annie Hall at the Oscars the next year. I know we don’t expect that kind of recognition for genre films, but it really does make me want to break china.)

Star Wars: A New Hope is pure mythology, distilled down to some of its simplest forms. Good and evil. Life and death. Triumph and defeat. Light and dark. When Lucas screened the film for a group of his friends and most of them shrugged their shoulders, Steven Spielberg had the measure of it. He told them all that the film would make a millions of dollars because of its “naiveté and innocence.” That those qualities were Lucas to a tee, and that he’d finally found the perfect medium to express them in. To most, those words of praise probably sound like a vote against—after all, who actually wants to be called innocent and naive? Who wants to create art and have it labelled that way? But it’s a mistake to knock those qualities on principle, just as it’s a mistake to insist that Empire Strikes Back is a better film simply because it’s “darker.” And it’s also a mistake to dismiss context, to wit—

—Star Wars was released two years after the Vietnam War ended.

To pretend that this had no bearing on the success of the first Star Wars film is far more naive than Spielberg accuses the movie itself of being. Vietnam marks a specific point in the American cultural consciousness, a definitive loss in the mind of the public, a war that destroyed the lives of so many young soldiers. It was also a war that was actively and broadly protested, largely by the country’s youth. That do-no-wrong brand of American zealousness, the sort touted by World War I clarion calls like “Over There,” was badly shaken.

And what of Star Wars? Is it any surprise that many Americans would be excited by a film where good and evil were easily grouped, where rebels go up against an Empire of oppression and fear? The story of a young farmboy, a princess, and a rogue who happen to fall together at just the right time, and bring the fight for galactic freedom one giant leap forward? Perhaps innocence isn’t really the best term, technically speaking. Star Wars is idealism personified, and it arrived at a time when it was desperately needed.

The truth is, we often turn our nose down at optimistic narratives when they are the hardest to pull off successfully. We expect the worst in others, we believe in sarcasm and worst case scenarios. We have no difficulty with the grim and the fatalistic and the fallen. Dystopia has been a undisputed ruler of fiction for years because everyone can find truth in it. We find it easy to imagine that the stuff of nightmares may come to pass. Getting people to buy the reverie? To believe in good unequivocally? That’s a magic trick of the highest order. That requires that we bypass every barrier created of cynicism, pragmatism, and expectation. It requires that a story reach deep down and contact the child in everyone.

When I was young, I adored Star Wars because it appealed to my code, my fundamental makeup, my wildest dreams. Now that I’m no longer that person, I love Star Wars because it reminds me of that little kid I used to be. It reminds me that I still need them.

And the reason that audiences were able to take Star Wars seriously was the because the people making the film were asked to take it seriously. So often before this (and indeed, before Star Trek), genre stories were performed with a necessary tongue-in-cheek quality. Very few were willing to treat these tales with a genuine candor. But the cast of this film somehow rolled themselves into an intensely perfect package. Every single actor is superbly suited to their role, and gives a performance above and beyond what was expected of them–and there are so many stories to that tune, too. Harrison Ford threatening to shove Lucas against a wall force him to read his own dialogue. Alec Guinness’ disdain for the entire project, and annoyance that audiences only knew him as Obi-Wan after it was released. The used car salesman accent that Lucas originally wanted for C-3PO, and Anthony Daniels’ smart suggestion to try a stuffy butler cadence instead. If no one had been willing to put in the effort, it would have been far easier to dismiss the film as a whole.

Star Wars captured people for being dirty and worn. Its design didn’t emerge from a singular shiny’n’streamlined retro-future play box; there was a cohesion to each place, each group, tied together by color palettes, sound, geometry, the intensity of light. The script is anything but poetry, but it is masterful in its ability to get out just enough information without being trite or tedious. It teases ideas that leave the audience curious and desperate for more—what are the spice mines of Kessel? What is this Academy that Luke is so insistent on attending? How does the Senate in this galaxy function? How did Leia end up a member of the Rebel Alliance?

The narrative is framed with precision and intention in mind—there are very few scenes in film history with the ability to manipulate quite so astutely as Luke staring off into a twin sunset, desperate for a more meaningful life. There are few battle sequences that find the same tension as the Rebel Alliance’s run on the Death Star. There aren’t many Western saloon scenes that can match the Mos Eisley Cantina for atmosphere and attitude. The film never spends too long in any one place, but it makes certain that all of its beats play out distinctly. It is wonderfully balanced as well; the droids’ antics pinball off of Obi-Wan’s grave demeanor which provides an easy counterpoint to both Luke’s earnestness and Han’s growing irritation.

I can’t talk about the film without mentioning the various special edition cuts that most fans are forced to watch. With each of the original trilogy offerings, there are drawbacks and improvements to the alterations. For this film, they’re fairly obvious; the additions to the Mos Eisley Spaceport are largely unnecessary, the added scene with Jabba provides context (but looks horrible in every edition), and the altered special effects for the final attack on the Death Star look excellent and genuinely make the battle easier to read. There’s also the “Han shot first” dilemma, which I am not going to get into, mostly because I feel like it’s an argument made for the wrong reasons. (Short version: I think Han should absolutely shoot first, but it seems to me that the majority of fandom wants it that way because they think it’s a testament to how cool Han is. And I don’t think Han is the cool guy. He’s funny and charming and likable, but he’s not cool.)

Each beat in the mythic narrative is nailed with an ease that should still make filmmakers envious. We casually discover our hero at a junk sale. He is helpfully saved by a wise guide who gives him a call to adventure. They encounter a sidekick/scoundrel who is only willing to help them in order to fix problems of his own. They are fortunately captured in the same place their cool-headed princess/resistance fighter is being held. And on and on it goes, without ever having to try over-hard to make the story move along. It gives the first film a lightness, a sense of wonder that is commonly unmatched in cinema. There is tragedy, yes, and profound tragedy at that. But for every terrible action there is one swing across a chasm by rope. There is one alien jazz song in a seedy spaceport bar. There is one panicked protocol droid crying over the death of his master by trash compactor, long after his counterpart has solved the problem.

Star Wars is a story that wears its influences on its sleeve, yet there are so many of them that it is hard to accuse the movie of being simply derivative or disingenuous. The combination of sources is too deft, too carefully woven. You can’t just read Joseph Campbell’s Hero With A Thousand Faces and understand everything Star Wars is about. You can’t watch one Kurosawa film and have its measure. You can’t sit through a Flash Gordon marathon and consider yourself wholly informed. You’d need so much more besides that: theology courses on Eastern and Western religions, an introduction to drag racing, World War II history, Frank Herbert’s Dune, opera, Arthurian legend, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, and 633 Squadron. All this and you’d barely scratch the surface. It’s not a random culling of sources–it’s a deliberate homage to storytelling as an artform.

Star Wars isn’t simply fun, or entertaining, or enjoyably distracting. Its idealism honestly doesn’t cover it either, even if that’s a significant part of its appeal. No, when we’re down to the most elemental tenets of story, Star Wars is precisely one thing: it is joyful.

And how often can we say that about the stories we love?

That’s really the secret sauce, in my opinion. We can pretend to profundity all we want, but we can’t prefer meaningful sadness every day of the week. It doesn’t make the smart, dark stuff any less important… we just see a lot more of it. While quality varies drastically across the board, there will always be more Breaking Bads. More Battlestar Galacticas. More Sopranos. But that first Star Wars film? It is a rare breed. And it is something that we need, desperately, the more jaded and critical we become.

This article was originally published in November 2015, as part of our Star Wars Movie Rewatch.

Emmet Asher-Perrin needs to swing across a chasm via rope just once. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.